CHAPTER 1

“The Himalayan glaciers are melting in Nepal and 1.5-degree limit is only possible if we; not reduce, not abate but phaseout fossil fuels.” UN Chief, COP28

1.1 Introduction

Numerous developing nations grapple with power shortages, and until FY2018, Nepal, despite its mountainous and landlocked terrain, was no exception. However, the country’s energy landscape has undergone a significant transformation since then, transitioning from an era of electricity crises to surplus. Recognizing energy’s pivotal role in national development, it is imperative that the government prioritizes its growth and sustenance through legislative frameworks, policy stability, and robust institutional support, while fostering a conducive environment for private sector participation. A reliable supply of electricity is fundamental to the prosperity and sustainability of any economy.

In Nepal, energy resources are categorized into three main types: traditional, commercial, and alternative sources. Despite the escalating demand for electricity, which increases by 10-15 percent annually, the incorporation of renewable energy into the national grid remains disproportionately low. Consequently, Nepal relies on electricity imports from India, particularly during the winter months when domestic deficits are pronounced. Despite possessing significant hydropower potential, only a fraction of it, approximately 5 percent, has been harnessed due to the complexities involved in investment. Biomass predominates Nepal’s energy mix, highlighting a concerning reliance on oil and LPG imports to meet energy needs. The transportation sector, a major consumer of energy, primarily relies on petroleum products. With the escalating costs of LPG and petroleum, the shift towards more cost-effective renewable sources becomes imperative. The development of hydropower projects and the exploration of alternative sources such as solar, wind, hydrogen, biogas, and biomass are critical long-term strategies to address the prevailing energy crisis.

Traditional energy production methods reliant on hydrocarbons cannot be hastily expanded in a sustainable manner. Pursuing such conventional approaches risks undermining economic gains through ecological degradation. Thus, the solution to the energy challenge lies in harnessing energy sources sustainably. International initiatives like SE4ALL underscore this approach, focusing on renewable energy sources and environmentally friendly technologies. Nepal’s participation in this initiative since FY2012 presents an opportunity to export clean energy to neighboring countries like India and Bangladesh, potentially replacing a significant portion of fossil fuel consumption.

CHAPTER 2

1.1 Current Situation

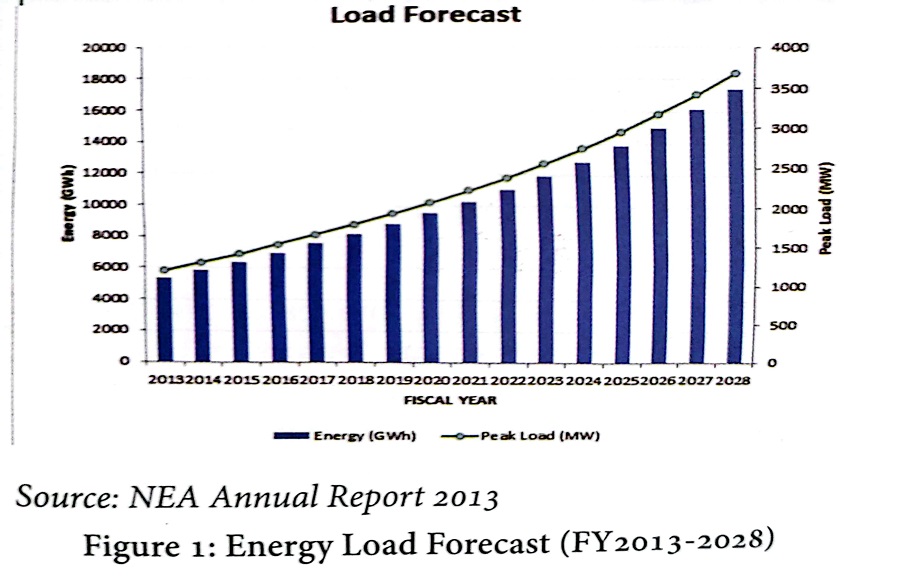

There is unanimous agreement among policymakers and experts that the swift adoption of clean energy is the sole remedy to confront the escalating reliance on fossil fuels within the country. In Nepal, both peak-power and annual energy demand have surged by 8 and 12 percent respectively, propelled by rapid urbanization and rural electrification efforts. Over the past seven years, energy consumption has nearly doubled; however, the per-capita electricity consumption of Nepalese stands at a modest 380 units, ranking among the lowest in Asia. Presently, approximately 93% of the population enjoys access to electricity, with a distribution ratio of 96% grid-connected consumers to 4% off-grid consumers. The Nepalese government-owned public sector entity, NEA, assumes the role of the primary supplier and distributor of electricity, operating within a monopolistic framework characterized by a ‘single buyer – single seller model.’ Projections based on the load forecast over the past decade and data from the Integrated Power System FY2023 reveal that the domestic power system’s peak load, inclusive of exports to India, exceeds 2500MW.

The Ministry of Energy, in collaboration with its implementing agency NEA, has established an ambitious goal for the upcoming 12 years: to quadruple the consumption of clean electricity.

1.1.1 Energy Generation

The collaborative efforts of NEA and independent power producers (IPPs) have yielded a total generation capacity of 2,684MW, primarily driven by hydropower, supplemented by solar, thermal, and bagasse sources. However, notable declines in hydropower output during dry seasons necessitate imports, whereas surplus energy during wet seasons facilitates exports to India.

Nepal views sustainable hydropower as pivotal to its transition towards clean energy, leveraging its abundant rivers for dam construction to meet energy demands domestically and for export to neighboring countries like India and Bangladesh. The Government of Nepal (GoN) is resolute in its commitment to advancing this agenda, embarking on multiple hydro projects and harnessing water resources for electricity generation as outlined in the Electricity Development Decade Plan. With substantial investments pledged by the GoN, private sector entities, Nepali migrants, foreign direct investments (FDIs), and through general public IPOs, NEA has allocated 90% of the national grid capacity to hydroelectric power.

1.1.2 Energy Transmission

The lack of clarity regarding transmission connectivity, both nationally and across borders, has raised concerns among power developers. Without adequate power evacuation infrastructure, many Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) concluded projects have been unable to commence construction. The FY2014 budget highlighted the prioritization of transmission line construction by the Government of Nepal (GoN). It became evident that without the addition of 200/400kV transmission lines, the existing grid capacity, primarily comprising 132kV lines, would be insufficient to accommodate additional megawatts of electricity for two key reasons: power evacuation and system stability.

In response, NEA has undertaken the development of several kilometers of high-tension lines and has laid out ambitious plans to construct over 1000 km of 200 kV and 400 kV transmission lines. These efforts aim to enhance the grid’s capacity, allowing for the transmission of over 300-400MW and 1,200MW of electricity through single-circuit lines, respectively.

1.1.3 Energy Distribution

NEA manages approximately 90% of power distribution in Nepal. Despite experiencing a high system loss of 24% in FY2013, NEA implemented rigorous measures to reduce it to less than 14% by FY2023. Discussions with NEA have revealed their openness to private-sector involvement in metering, billing, and transformer upgrading initiatives. Projects such as computerized billing and smart metering have been instrumental in implementing a standardized and improved billing system across all revenue collection centers of NEA, enhancing efficiency and cost-effectiveness. These initiatives have contributed to minimizing human errors during meter reading, reducing operational expenses, and fostering better relationships between NEA and its consumers.

1.1.4 Alternate Energy

In addition to hydropower, Nepal boasts significant renewable energy (RE) resources, including solar, various forms of biofuels, and wind, which can be harnessed to supply commercial energy to the national grid or rural communities. It is estimated that Nepal has the potential to develop over 100MW of micro hydropower, 2,100MW of solar power, and 3,000MW of wind power. Additionally, there is potential to install another 1.1 million domestic biogas plants.

The Government of Nepal (GoN) has responded to climate change with ambitious targets aimed at increasing the share of renewable energy in the energy mix to up to 10%. Multiple power purchase agreements (PPAs) have been concluded on solar and biomass energy between NEA and independent power producers (IPPs), demonstrating the significant potential of these sources to contribute to the renewable energy transition sector.

1.2 Situation Analysis

While Nepal boasts a high access rate of electricity at 95%, the quality of supply remains a pressing concern. To gain deeper understanding into the external dynamics shaping Nepal’s energy sector bottleneck and to pinpoint macro-environmental factors influencing its development, a PESTEL analysis proves invaluable. Despite widespread recognition of the necessity for investment, formidable barriers obstruct progress. These barriers span across political, legal, governance, institutional, commercial, and financing realms, all of which warrant thorough examination within the following framework.

Political : At the political level, fundamental differences and a lack of consensus persist regarding the use of natural resources and bilateral treaties concerning power trade. While new projects have been contracted, the Government of Nepal (GoN) has yet to finalize agreements for electricity exports to India surpassing 600MW. Conversely, the GoN has agreed to initiate 40MW of clean electricity trade with Bangladesh through a trilateral mechanism, contingent upon the approval of utilizing an 18km Indian grid connection linking Nepal and Bangladesh.

Economic : Electricity Tariff Fixation Committees (ETFCs) in Nepal are grappling with safeguarding public interests against electricity tariff adjustments. This inaction has severely impacted the creditworthiness of the Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA) in addressing foreign currency and payment risk guarantees. Operating as the single purchaser of electricity in a multi-seller market, NEA’s ability and willingness to pay during Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) negotiations significantly influences the bankability of independent power producers (IPPs). Discussions with the Nepal Bankers’ Association (NBA) revealed that collective guarantees from Nepali commercial banks only cover up to 100-150MW of hydropower generation, underscoring the necessity of international debt financing and foreign direct investment (FDI) as crucial external capital sources.

Social : Nepal’s labor market is characterized by rigidness and a lack of skilled workers, exacerbated by union-led unrest, posing significant challenges to investment. The GoN has struggled to develop energy market-oriented Technical Education and Vocational Training (TEVT) programs, which could potentially retain skilled youth from seeking employment abroad.

Technological : Public institutions in Nepal have neglected research and development (R&D) culture and technology transfer, hindering innovation. Restrictions on international tech startups investing in the country have further stifled technological advancements. Additionally, the absence of proper energy storage technology for power generated from alternative sources during off-peak hours discourages the construction of new projects. However, the recent approval of the ‘NEA IT Policy 2023’ enables the Corporation to introduce digitalization through online portals and mobile applications for bill payments, complaint reporting, and accessing information on power supply.

Environmental : Nepal faces heightened climate risks despite its negligible contribution to greenhouse gas emissions. Natural calamities along Himalayan rivers and hydrological changes have impeded many hydropower operations and compromised national grid stability. The country’s struggle with transmission infrastructure facilities is exacerbated by Right of Way issues, causing power evacuation delays due to deforestation of rainforests.

Legal : While legislation such as the Hydropower Policy 1992 and Electricity Act 1993 encouraged participation in electricity generation, subsequent policy revisions have encountered setbacks. The Electricity Act 2008 went unendorsed by Parliament, and a withdrawal from the National Assembly by the energy minister in FY2022 further complicated the regulatory landscape.

NEA’s monopoly and the absence of a cartel in the energy market have raised governance concerns, while the sensitive topic of resource unbundling has been hindered by strong trade union opposition.

CHAPTER 3

3.1 Energy Consumption

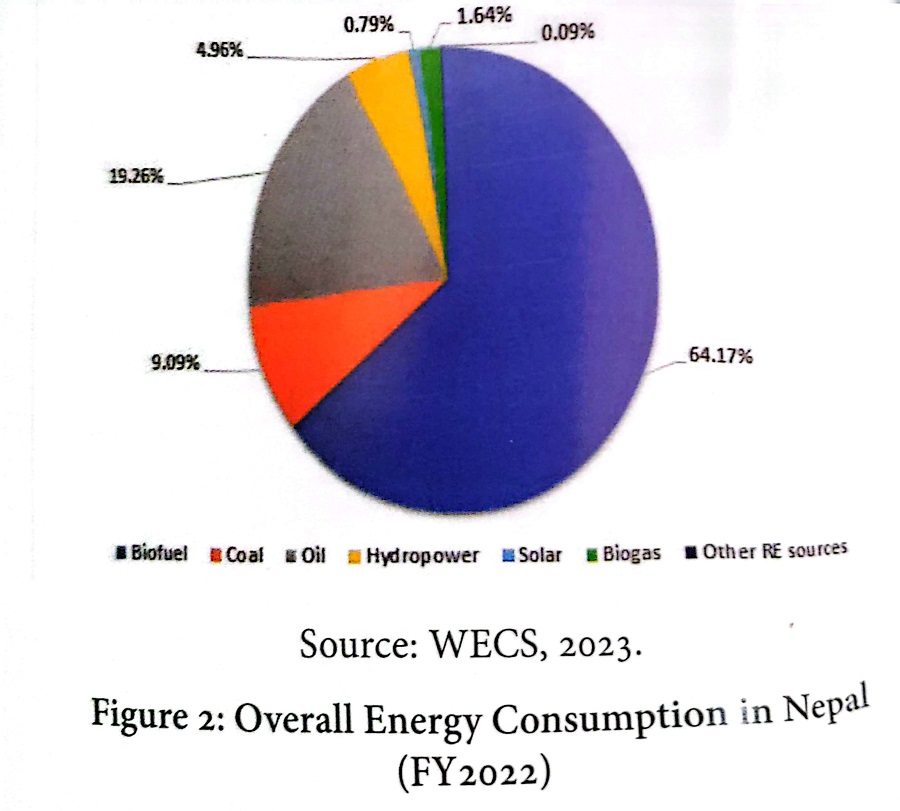

Scenario Energy consumption in Nepal during FY2022 reached to 640 Picojoules, largely dominated by biofuels in the form of firewood, agricultural waste and animal dung. The commercial fossil fuels (petrol, diesel, LPG, coal, etc.) has been consistently increasing with the share of 28.35%, while hydropower connectivity to the electricity grid has also been accounted on the increasing trend for coming FY. Unfortunately, alternate energy contribution to the total energy mix has been minimal of 2.5% but observed on more increasing pattern than commercial fuels.

3.2 Sustainable Energy for Nepal

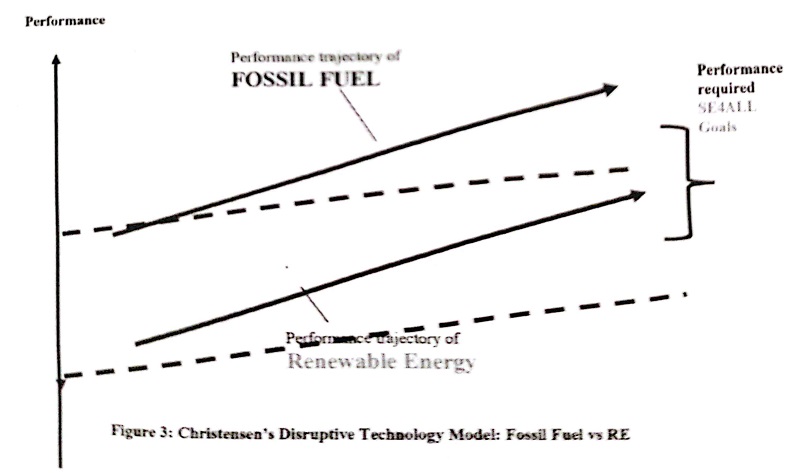

Policy and regulatory unpredictability consequent to political uncertainty, sub optimal utilization of government budget, limited capacity of institutions, labor issues and limited access to finance are the common concerns faced by energy sector in the country that need to be addressed to promote SE4ALL. Based on a certain scenario projection for the Nepalese economy to meet the country’s development needs of 26% energy mix by 2030, is required from the clean electricity. Christensen’s Disruptive Technology Model (1995) describes how new RE technology expansion can lead an energy industry of Nepal and transform the way their product/services are delivered from fossil fuel dependency.

Innovation in RE has been induced by a demand pull (climate change) or supply push as new technology typically arrives in the market as a ‘bundle of possibilities’. Nepal to achieve SE4ALL initiative Net-Zero by 2045, rigorous progress should be made on the Action Areas platform and its linkages. Today, RE capture (including hydropower) in the market has a very low performance (below 10%); thus, GoN should put an effort through assembling dynamic capabilities to steadily improve their market share against fossil fuel.

3.3 Recommendations on Transforming the Sustainable Energy Ecosystem

The external diagnostic tools discussed in earlier chapter elaborates that the RE business environment in Nepal has been more static and require new ways of thinking with continuous improvement. In the country with increased level of uncertainty on fossil fuel, the framework comprising of dynamic capabilities Sensing, Seizing, and Shaping should be beneficial for the transformation of RE’s competitive advantage. Therefore, GoN has to concentrate on enabling the following implications for scenario planning of possibilities, utilizing the resources, and eventually architecting the idea and constructing real-world outcome.

3.3.1 Promoting electricity for Cooking

Electricity for cooking is a very important aspect for mitigation measures, adaptation and convenience building. As GoN sets a target to increase electric cooking for 25% household, this initiative can definitely reduce some extent of $500million LPG import cost. After upgrading residential infrastructure to higher capacity, NEA needs to install Time of Use (TOU) meters for charging different rates during peak hours and minimizing the high loss of generation during off-peak hours.

3.3.2 Utility-Scale Alternate Energy Solutions for Energy Mix

Solar Power

Nepal is blessed with more than 300 days of sunshine and a right condition for Solar energy generation. However, the 770MW survey license of the developers are still in dilemma because (i) discouraging PPA rates (reverse model) (ii) green land availability (iii) grid connectivity (iv) knowledge among policy makers.

Therefore, without encouraging PPAs, policy subsidies, infrastructure connectivity for transmission and storage of energy, the economics of solar power development won’t be competitive for sustainable solution. One wild idea, in absence of green land an innovative cutting-edge technology as Floating Solar Panels can be possibly adopted by IPPs over the wetlands.

Wind Power

Although, some potential areas have been identified from both the government and private sectors, lack of power evacuation and policy for purchasing of the electricity has been a bottleneck. Small scale wind power is going to grow exponentially during winter season in Nepal (hydro-dry season); thus, NEA should allow wind power connection to the grid and explore the possibility of netmetering because individuals can sell excess energy back to the utility.

Biomass & Biogas

Nepal has done a sizeable progress in replacing coal by briquettes and pellets produced from aboveground air-dried biomass available on the forest’s landmass. According to CBS report, total solid waste generated by 276 municipalities in Nepal annually, around 39% is organic waste. Using incinerator technology such organic waste can be converted to biogas (waste-to-energy) on PPP model to reduce partial import of LPG.

3.3.3 Expansion of the Grid Infrastructure

NEA’s concentration has mainly been the run-of-the-river type projects that generate maximum hydroelectricity during monsoon but production goes down drastically in subsequent months. To further reduce fossil fuel trade deficit with India, GoN has to rigorously pursue diplomacy channel to sell excess electricity not being restricted to any MW figures. Another wild idea can be on paving the partnership for electricity trade with land connecting neighbor, China, which can certainly bolster Nepal’s foreign currency exchange.

NEA should work to prepare an action plan for attracting private sector to construct transmission line projects under the BOOT model following suitable international examples. The plan can also define to what extent the role and capital of the private sector can be accepted for the development of transmission infrastructure in the country.

3.3.4 Large Scale Renewable Energy for Electricity

GoN policies and regulatory regime mentioned in the earlier chapter, need to be supported by an appropriate institutional mechanisms and mindset that respects the role of all stakeholders. Nepal should adapt the experience from other countries on developing a special purpose vehicle for feasible hydropower projects with identified land, clearances and PPAs. Without deny, Nepal’s electricity market needs multiple buyers because the state-owned NEA run by employees instead of entrepreneurs simply lack a strong motive to energy transition.

3.3.5 Sectoral Outlook for Reduction in Oil Consumption

Transportation

According to Nepal Economic Forum report, in FY2023/24, Nepal has increased the EV import by threefold making sales second largest in the world. This is encouraging news; however, in contrast NEA has only established 100 operational charging stations in the country. To support the infrastructure demand for EV’s, GoN should involve private sector for construction of additional charging stations. Nevertheless, the GoN target by 2030 to provide electric public transportation i.e., Bus Transit System should enable citizens to limit the petroleum products usages.

Agriculture

Agriculture is a second largest sector to consume much of imported diesel in Nepal and the trend is alarmingly increasing. AEPC can ensure subsidy program and banks can offer micro-financing options for the possibilities of implementing some efficient and clean technologies (wind farm and geothermal heating) or by promoting/safeguarding the traditional agricultural practices.

Industrial Sector

The decision by the NEA to supply clean electricity to factories round the clock through dedicated feeders by charging double tariff (during dry season) has to be taken positively. The overall tariff measured by Time-of-Day meter has been more economical than consumption of energy from fossil fuels such as coal or diesel generators. As RE generation on-grid increases, subsidy on electricity tariff with more dedicated feeders can be supportive impact for the future expansion of industries.

CHAPTER 4

4.1 Introduction of Disruptive Technology

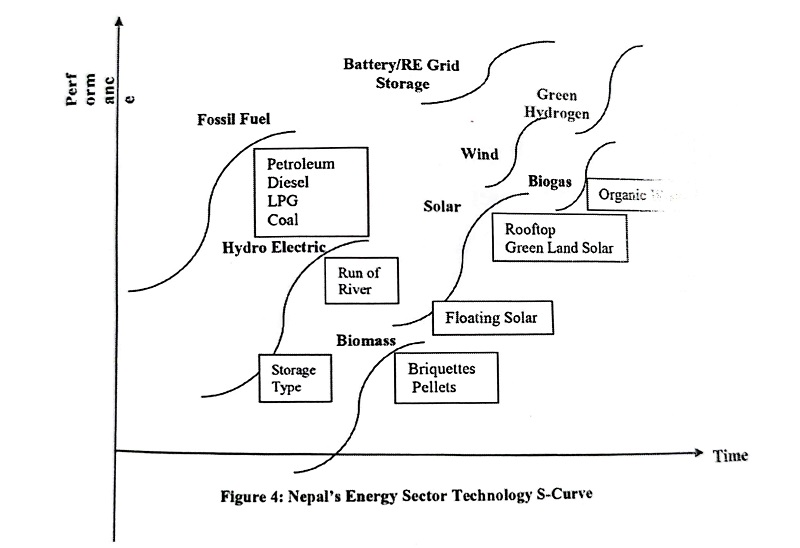

According to Geroski (2003), S-Curve is a technological lifecycle, once reaches separation, a new innovation is required with greater efficiency, which might create another S-Curve. In Nepal, different technology S-curves recognized below elaborates RE business positioning and can be better explored on the future performance for growth horizon.

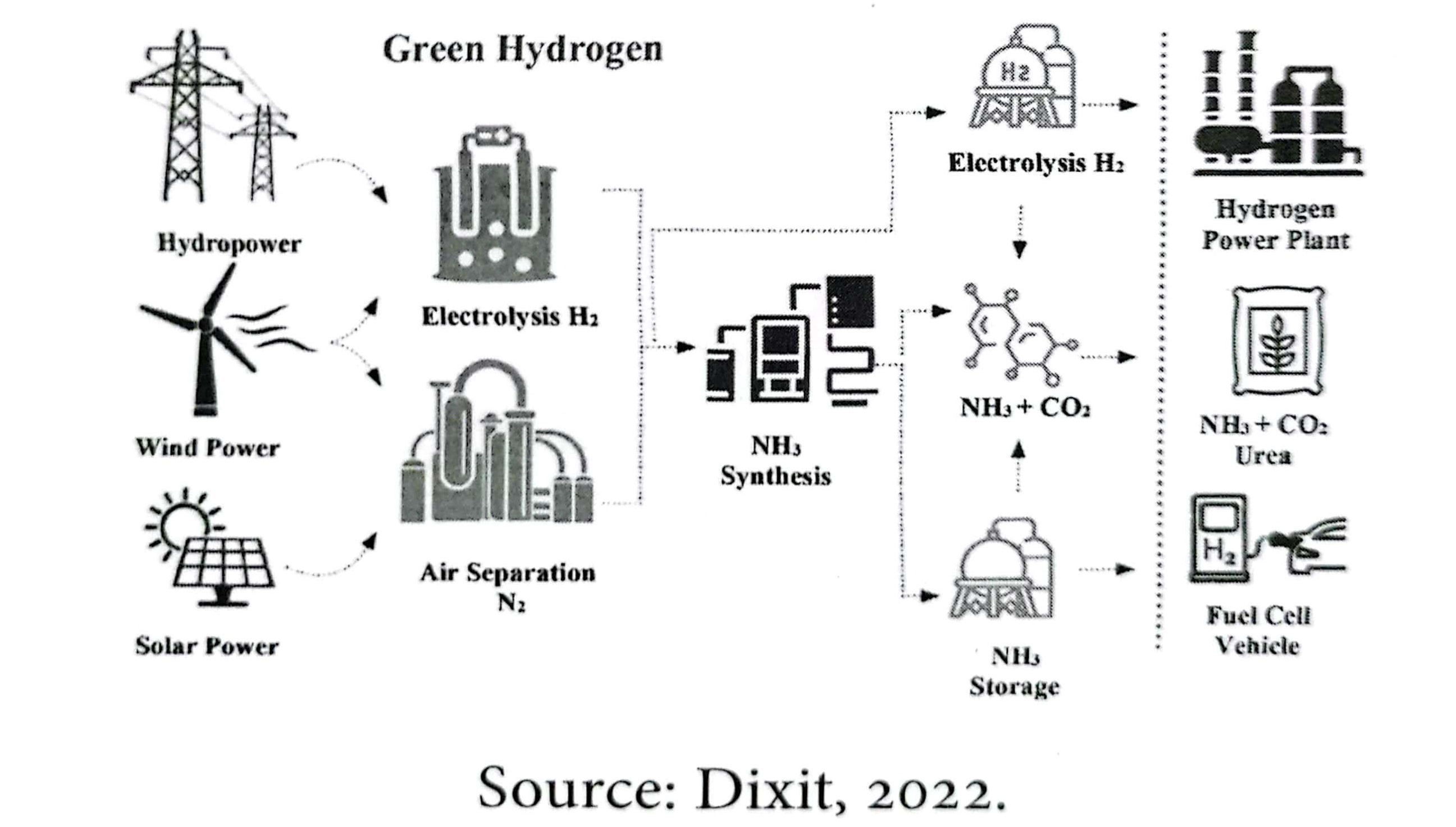

Fossil fuels have always been at the foundation of energy technology; however, over the period there has been a paradigm shift to the clean energy value chain. Considering the fossil fuels to phase out by FY2045, Nepal has always witnessed its dominancy for decades in RET from biomass and run-of-river hydroelectric power. Gradually in the past 20years, solar energy technology has increased popularity on the rooftop and fractional connectivity from green land to the grid has marked it as a suitable dominant design. Outlined over the earlier chapters, the bottleneck with hydropower development as for the huge investment, climate vulnerability and likewise absence of green land for solar can restrict the aim of 26% energy mix by FY2030. Introduction of the carbon free oil for 21st century, Green Hydrogen energy has very abundant claim on the S-Curve as a new entrant and to prove itself as a scalable future disruptive technology in Nepal.

Hydrogen is the carrier of energy and a largest used commodity in the world. Grey Hydrogen is produced through electrolysis of water powered by fossil fuel; however, if CO2 captured and stored, is renamed Blue Hydrogen. On the other-hand, hydrogen produced through renewable electricity is referred to as a Green Hydrogen, which will ultimately prevail due to lower cost and zero carbon emission.

In Nepal, GH2 can be a vector connecting electricity carrier and the commodity excelling to succeed as a dominant design. At the onset, GH2 can be produced by exploiting clean electricity which has been choking on the grid that IPPs cannot sell to the NEA. Further, GH2 has an immense potential to be utilized in industrial applications (steel, cement, mining) to generate income, fuel for decarbonizing transportation, ammonia-based fertilizers and possibly supply power through smart grid.

Source: Dixit, 2022. Figure 5: Green Hydrogen Possibilities in Nepal

Source: Dixit, 2022. Figure 5: Green Hydrogen Possibilities in Nepal

4.2 Scaling Inclusive Innovation

Inclusive innovation solutions for increasing climate risk and energy life-cycle challenges faced in Nepal should be addressed by development of the new business model and scaling up of the GH2 production. ‘Green hydrogen is the technology for many and not just few’. Following framework should be suitable to define how energy stakeholders in Nepal can use this disruptive technology as a tool towards benefiting people in a positive direction and allow them to have better opportunity for future.

In developing economy Nepal with abundant RE (hydropower), inclusive innovation framework will be helpful in understanding the current perspective and what it takes to establish GH2 economy. To produce GH2 competitively and introduce it to the energy ecosystem, there should be ample of RE resources available at a discounted rate. As compared to solar technology two decades earlier, GH2 can be an expensive option due to emerging new innovation. However, GoN efforts to strategically execute National Hydrogen Initiative can ensure possibility of GH2 development as a viable alternative to fossil fuel in the country.

4.3 Non-Market Concerns for Green Hydrogen Development

Referring to the external market environment to meet the energy transition goals in Nepal, GH2 is being evaluated as a political future fuel to put the pause on carbon emission. Nevertheless, the initial challenge will be to understand and deal with the non-market environment impacting the development: who the stakeholders are, what do they want, how are they connected and gradually what is that the stakeholders can do to influence.

GoN recently (FY2024) has endorsed the National Green Hydrogen Policy outlining indicative directives such as tax and VAT incentives, import discounts, provide discounted electricity tariff and allow provision to build own RE project for GH2 production. Towards the next step, as GoN is expected to establish regulatory framework on production, storage and transmission of GH2; NEA can provide electricity similar to irrigation subsidized rates. This can motivate domestic ammonia fertilizer production at lower cost, giving certain break to trade deficit. Prime Minister of Nepal has indicated interest to ride hydrogen vehicle, which has come out as diplomatic message for establishment of the FCEV value chain at KU Hydrogen Lab, including charging station.

CHAPTER 5

5.1 Conclusion

Looking ahead, Nepal has to realize tremendous effort to further address the impact from climate change challenges by adopting transition to more sustainable energy ecosystem. To enhance paradigm shift towards RE and to obtain constant energy security, an advanced grid battery storage system should be reliable and economically viable option to minimize dependency on the fossil fuel. Beginning of the FY2024, Nepal has signed a long-term trade agreement with India confirming export of 10,000MW electricity within a decade and also allowing usage of Indian grid to transmit Nepal’s power to Bangladesh. This cooperation shall definitely foster all the stakeholders to fulfil the expectation drafted in the 12th year plan towards unbundling investment and clean energy development challenges.

On the other-hand, GH2 policy definitely has provided an enabling environment for developers addressing Nepal as an attractive destination for GH2 production and investment. Nonetheless, GoN with the right vision and leadership should establish, Green Hydrogen Development Board to deal with mega projects to develop hydrogen from hydropower over coming years and possibly also advocate for the cross-border trade.

In summary, balance between Exploiting Renewable Energy and Exploring Green Hydrogen in the coming years, is the creditable strategy for Nepal in making sustainable energy ecosystem optimum, more efficient and more reliable.

The writer of this article is a Consultant in Energy & Infrastructure Development in Asia, Said Business School - University of Oxford. This research-based article is taken from the 6th issue of Urja Khabar, a bi-annual magazine. Which was Published on 15 June, 2024

REFERENCES