KEY HIGHLIGHTS:

1. Global Climate and Carbon Agenda: Pre and Post-Paris Agreement

2. Global Climate Funds and Mechanisms

3. Regulatory and Compliance-based Carbon Markets

4. Overview of Nepal’s Renewable Energy-based Carbon Projects

5. COP 29’s Implications for Climate Financing for Least Developed and Developing Countries

6. Future Perspectives of Carbon Projects under Article 6

1. Global Climate and Carbon Agenda: Pre and Post-Paris Agreement Era

The awareness of the effects of climate change was further advanced at the second World Climate Conference held in Geneva, Switzerland, from 29 October to 7 November 1990. The conference stated that climate change was a global problem for which an international response is required. The 1992 General Assembly in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, emphasized the urgency of immediate international action on the environment, including climate change. The Earth Summit set a new framework for seeking international agreements to protect the integrity of the global environment in its Rio Declaration and Agenda 21, which highlighted global consensus on development and environmental cooperation. The most significant event during the conference was the opening for signature of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC); by the end of 1992, 158 states had signed it. It entered into force in 1994, and in March 1995, the first Conference of the Parties (COP) was held in Berlin, launching talks on a protocol or other legal instrument containing stronger commitments for developed countries and those in transition.

The major milestone of climate change action was initiated in December 1997 with the Kyoto Protocol to the UNFCCC, the most influential climate change action so far taken. It aimed to reduce the industrialized countries’ overall emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases by at least 5 percent below the 1990 levels in the commitment period of 2008 to 2012. The Protocol, which opened for signature in March 1998, came into force on February 16, 2005.

To make climate action more ambitious, voluntary, and open to global participation, 196 parties at COP 21 in Paris on December 12, 2015, signed a legally binding international treaty on climate change, which is known as the Paris Agreement. The main goal of this agreement is to limit global warming to well below 2, preferably to 1.5 degrees Celsius, compared to pre-industrial levels. To achieve this long-term temperature goal, countries aim to reach global peaking of greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible to achieve a climate-neutral world by mid-century. The Paris Agreement is a landmark in the multilateral climate change process because, for the first time, a binding agreement brings all nations into a common cause to undertake ambitious efforts to combat climate change and adapt to its effects.

The Paris Agreement works on a 5-year cycle of increasingly ambitious climate action carried out by countries. The countries submit their plans for climate action, known as nationally determined contributions (NDCs), by 2020. In their NDCs, countries communicate actions they will take to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions in order to reach the goals of the Paris Agreement. Countries also communicate in the NDCs actions they will take to build resilience to adapt to the impact of rising temperatures. To detail the efforts towards the long-term goal, the Paris Agreement directs the countries to formulate and submit by 2020 long-term low greenhouse gas emission development strategies (LT-LEDs). It provides the long-term horizon to the NDCs but is not mandatory. For the tracking of the progress, the Paris Agreement has established an enhanced transparency framework (ETF). Under ETF the countries will report transparently on actions taken and progress in climate change mitigation, adaptation measures, and support provided or received. This reporting as per ETF started in 2024, and every country has to submit it to the UNFCCC. The information gathered through the ETF will feed into the Global Stocktaking, which will assess the collective progress towards the long-term climate goals. Further, this will lead to recommendations for countries to set more ambitious plans in the next round.

The 1992 General Assembly in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, emphasized the urgency of immediate international action on the environment, including climate change.

Many countries, regions, cities, and companies are establishing carbon neutrality targets. Zero-carbon solutions are becoming competitive across economic sectors. Currently, the trend is most noticeable in the power and transport sectors and has created many new business opportunities. The Paris Agreement 2015 formulated three different carbon trading avenues. They are

• Article 6.2: Accounting guidance for reporting of “internationally transferred mitigation outcomes” (ITMOs) with “corresponding adjustments.”

• Article 6.4: An emissions mitigation mechanism to issue units for programs or activities, building on existing Kyoto mechanisms (CDM).

• Article 6.8: Work program for non-market approaches to advance cooperation that does not involve ITMOs.

2. Global Climate Funds and Mechanisms

Climate finance is the mobilization of financial resources to help implement mitigation and adaptation in developing countries to minimize the impacts of climate change. The fund can be of public climate finance commitments by developed countries under the UNFCCC or through bilateral, as well as through regional and national climate change channels and funds. In the 2009 Copenhagen Accord, developed countries guaranteed to deliver climate finance of USD 30 billion between 2010 and 2012. The Paris Agreement repeats that developed countries should take the lead in mobilizing climate finance “from different sources, instruments and channels,” and COP21 in 2015 agreed to set a new collective goal by pledging USD 100 billion by 2025. Many countries have highlighted the need to increase international support in implementing their National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) and Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

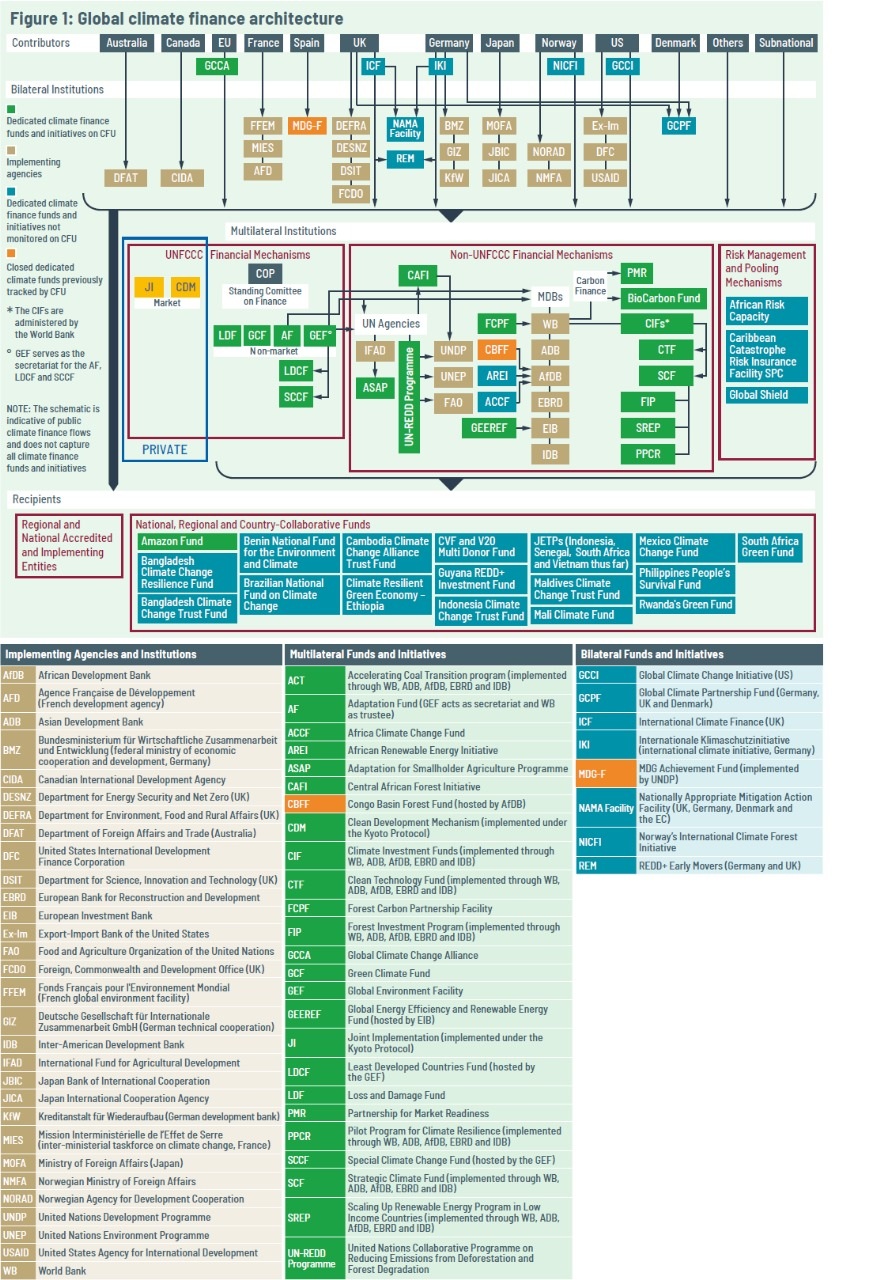

Figure 1 provides a synopsis of the worldwide climate financing mechanism. The different types of climate finance available are in the form of grants, concessional loans, guarantees, private equity and technical assistance.

3. Carbon Markets: Regulation & Compliance

Two types of carbon markets exist: regulatory compliance and voluntary markets. The compliance market is used by companies and governments that, by law, have to account for their GHG emissions. It is regulated by mandatory national, regional, or international carbon reduction regimes. On the voluntary market, the trade of carbon credits is carried out voluntarily. The size of the two markets differs considerably.

3.1 Regulatory Compliance Market:

The International Regulatory Compliance Market is established by the Kyoto Protocol that implemented three mechanisms, namely the International Emission Trading, Joint Implementation (JI) and Clean Development Mechanism (CDM).

Summary of International Regulatory Compliance Markets under Kyoto Protocol (KP)

Under International Emission Trading, parties with commitments under the Kyoto Protocol (Annex B Parties) have accepted targets for limiting or reducing emissions. These targets are expressed as levels of allowed emissions, or assigned amounts, over the 2008- 2012 commitment period. The allowed emissions are divided into assigned amount units (AAUs). Emissions trading, as set out in Article 17 of the Kyoto Protocol, allows countries that have emission units to spare - emissions permitted them but not “used” - to sell this excess capacity to countries that are over their targets. Thus, a new commodity was created in the form of emission reductions or removals.

The mechanism known as “joint implementation,” defined in Article 6 of the Kyoto Protocol, allows a country with an emission reduction or limitation commitment under the Kyoto Protocol (Annex B Party) to earn emission reduction units (ERUs) from an emission-reduction or emission-removal project in another Annex B Party, each equivalent to one tonne of CO2, which can be counted towards meeting its Kyoto target.

The Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) defined in Article 12 of the Protocol, allows a country with an emission-reduction or emission-limitation commitment under the Kyoto Protocol (Annex B Party) to implement an emission-reduction project in developing countries. Such projects can earn saleable certified emission reduction (CER) credits, each equivalent to one tonne of CO2, which can be counted towards meeting Kyoto targets. The mechanism stimulates sustainable development and emission reductions while giving industrialized countries some flexibility in how they meet their emission reduction or limitation targets.

3.2 Voluntary Carbon Market:

The voluntary carbon markets function alongside compliance schemes and enable companies, governments, non-profit organizations, universities, municipalities, and individuals to purchase carbon credits (offsets) voluntarily. Currently, the majority of Voluntary Carbon Credits (VCCs) are purchased by the private sector, where corporate social responsibility goals are typically the key drivers.

Market participants use carbon credits to offset emissions that are caused by their activities and cannot or have not yet been eliminated. Firms across the globe either utilize VCCs that are sold by registries (primary markets) or enter into VCC derivatives contracts (secondary markets). The global nature of voluntary carbon markets allows investments to be made anywhere in the world to develop new, innovative sequestration technologies or to preserve critical habitats or forests by creating a market-based incentive through the growing demand for carbon offsets.

Some of the Voluntary Market Registries are:

American Carbon Registry (ACR): https:// americancarbonregistry.org Gold Standard Registry: https://www. goldstandard.org/resources/impact-registry Climate Action Reserve (CAR): https://www. climateactionreserve.org/ Social Carbon Registry: http://www.socialcarbon. org/developers/registry/ Plan Vivo Registry: http://www.planvivo.org/planvivo-certificates/markit-registry/ Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) Registry: https:// verra.org/project/vcs-program/ Climate, Community, & Biodiversity Standards (CCBS) Registry: https://verra.org/project/ccbprogram/

4. 4. Overview of Nepal’s Renewable Energybased Carbon Projects

The Alternative Energy Promotion Centre (AEPC) succeeded in registering its first Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) project as early as December 2005. Simultaneously, two bundled CDM projects on biogas (Biogas Support Program-Nepal Activity-1 and Biogas Support Program-Nepal Activity-2) were registered with UNFCCC on the same day. This was a landmark portal for Nepal in the international carbon markets, and since then, the AEPC has been capitalizing on the carbon opportunities. Being an apex institution for renewable energy and energy efficiency promotion in Nepal and citing the contribution of renewable energy for climate change mitigation and adaptation, the AEPC realizes that the scope needs to be expanded beyond the horizon of mitigation, which also encompasses the adaptation in its domain.

So far, a total of eight carbon PAs/PoAs have registered in the UNFCCC CDM registry, of which five domestic biogas projects and three projects are of Micro Hydro Promotion, Improved Cooking Stove and Improved Water Mill. Details of projects are shown in the table below.

The maximum emission reduction capacity of these eight projects is 810,633 Certified Emission Reduction (CER) per year. The details of emission reductions from the AEPC CDM projects are as follows:

AEPC biogas projects are also registered in the Gold Standard registry. The Biogas PoA was registered as the first AEPC project in Gold Standard on January 31, 2013, followed by Biogas PA on August 1, 2018.

As per the Annual Progress Report, around 5.94 million units of Emission Reduction (ER) have been generated and an additional 542,866 ERs verifications are under Gold Standard Registry Review (A total of 6.5 million units of Emission Reductions); and around 6.48 million units of ERs have been sold. The total earnings from carbon revenue are around USD 35.27 million.

Nepal has minimal carbon projects compared to the other countries in the world. In the clean development mechanism registry, the activity projects that are requested for the transition to Article 6.4 are eight government projects and are operated by AEPC. Similarly, AEPC projects are active in the gold standard registry, which is about 0.2 million biogas plants. From other institutions, 114 carbon projects are registered in the Gold Standards, most of the projects are biomassrelated projects. Out of these, 23 carbon projects are listed and are in process of getting registration in the Gold Standard registry. Under the Verra Registry, there are eight projects registered at the Government of Nepal, which are mostly biomass projects. During COP 29, Nepal’s government has signed an agreement with the Swedish Energy Agency (SEA) to develop the carbon project under Article 6.2. SEA is interested to developing the large biogas project with the AEPC. Some level of preliminary preparation has been done for the large biogas project development by SEA.

5. COP 29: Climate Finance for LDC & DC Countries

The recent COP 29 was held in Baku, Azerbaijan, from 11th November 2024 to 22nd November 2024 and emphasized establishing a new climate finance goal, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, building resilient communities, ensuring means for stronger climate action in countries, and guiding the country to develop NDCs. The major achievements of COP 29 in relation to climate financing for developing countries are:

• Triple financing to developing countries, from the previous goal of USD 100 billion annually to USD 300 billion annually by 2035.

• Secure efforts of all actors to work together to scale up finance to developing countries, from public and private sources, to the amount of USD 1.3 trillion per year by 2035.

A notable achievement in mobilizing Article 6 is that countries have agreed on the final building blocks, which set out how carbon markets will operate under the Paris Agreement, making country-to-country trading and a carbon crediting mechanism fully operational. Similarly, in the case of Article 6.2, COP 29 has shown clarity on how countries will authorize the trade of carbon credits, and tracking of registries will be done. Further, it has emphasized assuring the environmental integration prior to the project implementation.

The countries agreed on standards for a centralized carbon market under the UN (Article 6.4 mechanism). The developing countries will benefit from new flows of finance, and particularly the least developed countries will get the capacity-building support to move ahead in the market. Moreover, the parties have handed over the todo list for 2025 to set up the new carbon crediting mechanism.

6. Future of Carbon Projects under Article 6

With the Article 6 mechanism, the country can now access carbon financing through carbon trading through Article 6.2 (cooperative approach) and Article 6.4 (market mechanism). This has widened up the opportunities to access more carbon financing in the country. With the ambitious NDCs of the developed countries, it is expected to increase investment in clean/renewable/energy-efficient technologies and increase the demand for emission reduction units in the future. Understanding the beneficial side of carbon trading, the participation of public and private entities in the Article 6 mechanism will increase in coming years. In the future, more innovative projects and clean technology projects will be developed in the developing countries. This Article 6 mechanism will attract investment from private sectors and banking sectors in clean technology, renewable energy, and energyefficient technologies.

The author is currently working as deputy director at the Alternative Energy Promotion Center (AEPC), under the Ministry of Energy, Water Resources and Irrigation, Government of Nepal. The opinion expressed in this article is solely based on the author’s personal views and does not represent the author’s organization. This article is taken from the 7th issue of Urja Khabar, a bi-annual magazine. Which was published on 7 January, 2025.

The author is currently working as Director at the Alternative Energy Promotion Centre (AEPC), Ministry of Energy, Water Resources and Irrigation, Government of Nepal.